the taste code of Xinjiang roasted buns

The flame poem in the pit: the taste code of Xinjiang roasted buns

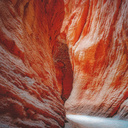

At the corner of the maze in the old city of Kashgar, a mass of white fog was wrapped in wheat and meat. When the copper cover of the Yellow Ninang Pit was lifted, thirty golden warrior-like baked buns stretched their muscles in the residual temperature of charcoal fire, and the shiny skin reflected amber luster in the sun. This Xinjiang cuisine, known as Shamusa, is telling the most touching taste legend on the Silk Road with the most primitive art of fire.

First, the flame sculpture in the desert

The making of baked buns is an accurate art of temperature behavior. At four o'clock in the morning, Master Wu Maierjiang began to knead the dough. This dough without baking powder will form a unique crisp armor at high temperature. Mutton must be taken from the lamb slaughtered on the same day, and the ratio of fat to thin is accurate to three or seven points, and it meets the leather teeth (onions) nourished by Tianshan snow water in a wooden basin. When the master throws the dough into a perfect quadrangle and his fingertips fly over, the meat stuffing and dough have reached a golden ratio.

The real climax began in front of the pit. Sticking to the wall, the steamed stuffed bun experienced metamorphosis at 300 degrees, and the dough was quickly dehydrated under charcoal fire, forming a slightly charred hard shell, while the inner layer became flexible and stiff under the action of steam. This two-day tempering of ice and fire gives the baked buns a contradictory aesthetic feeling of crisp outside and tender inside. At the moment when the copper hook went into the pit, thirty baked buns, such as golden meteors, fell into the tray, and the fine focal spots on the surface were like wind erosion lines in the Taklimakan desert.

Second, the taste genes of nomadic civilization

The shape of baked buns hides the survival wisdom of nomadic people. The quadrilateral structure is not only convenient to attach to the pit, but also symbolizes the awe of the square world. The application of dead dough originated from the demand of ancient business travelers for portable dry food, which can be stored on hunchbacks for half a month without being bad. The addition of sheep tail oil is not only a flavor code, but also a survival strategy to cope with extreme cold. Every bite of oil is an energy reserve for crossing the Gobi.

On Bazaar in Hotan, the steamed stuffed bun chef will brush the egg yolk liquid on the surface to form a golden red luster; The craftsmen in Kashgar carved diamond patterns with needles to allow the heat to penetrate evenly. These subtle differences, like the dialects of the thirty-six countries in the western regions, maintain their unique personalities in similarity. When nomads sit around the campfire and share the baked buns, the moment when the hot gravy burns the tip of their tongue is the song of their life against the harsh environment.

Third, the blending of civilizations on the tip of the tongue

Along the track of the ancient Silk Road, the baked buns have quietly changed. In Samarkand, it was wrapped in a cheese coat; In the west city of Chang 'an, Hu merchants added Chinese spices to the stuffing. Today's Urumqi night market, there is a rebellious version of crayfish stuffing, and Chili and cumin have reached a wonderful reconciliation in the dough. This kind of taste dialogue across time and space makes roasted buns a living fossil of civilization.

In the modern kitchen of the International Grand Bazaar, the infrared thermometer monitors the temperature of the pit, but the master still insists on feeling the heat with the back of his hand. Chain fast food restaurants have launched vacuum-packed baked buns, but they have never been able to replicate the soul of firewood. When urban white-collar workers cut the baked buns with knives and forks, Tajik elderly people are still grabbing food directly with their thick palms, and the two gestures are demonstrating the evolution and persistence of tradition in the same time and space.

In the old city of Kashgar at dusk, the last batch of baked buns is being taken out of the pit. The burnt incense overflowed the curtain of Adelaide silk and rose with the sound of Dutar piano. In this era of machine copying delicious food, baked buns still stubbornly maintain the original memory of the flame. Every hot triangle wrinkle seals the sun, sand and the eternal desire of human beings to fight against time in the western regions. When the tip of the tooth breaks through the brittle boundary and the hot gravy pours into the mouth, we swallow not only food, but also a whole flowing civilization epic.

At the corner of the maze in the old city of Kashgar, a mass of white fog was wrapped in wheat and meat. When the copper cover of the Yellow Ninang Pit was lifted, thirty golden warrior-like baked buns stretched their muscles in the residual temperature of charcoal fire, and the shiny skin reflected amber luster in the sun. This Xinjiang cuisine, known as Shamusa, is telling the most touching taste legend on the Silk Road with the most primitive art of fire.

First, the flame sculpture in the desert

The making of baked buns is an accurate art of temperature behavior. At four o'clock in the morning, Master Wu Maierjiang began to knead the dough. This dough without baking powder will form a unique crisp armor at high temperature. Mutton must be taken from the lamb slaughtered on the same day, and the ratio of fat to thin is accurate to three or seven points, and it meets the leather teeth (onions) nourished by Tianshan snow water in a wooden basin. When the master throws the dough into a perfect quadrangle and his fingertips fly over, the meat stuffing and dough have reached a golden ratio.

The real climax began in front of the pit. Sticking to the wall, the steamed stuffed bun experienced metamorphosis at 300 degrees, and the dough was quickly dehydrated under charcoal fire, forming a slightly charred hard shell, while the inner layer became flexible and stiff under the action of steam. This two-day tempering of ice and fire gives the baked buns a contradictory aesthetic feeling of crisp outside and tender inside. At the moment when the copper hook went into the pit, thirty baked buns, such as golden meteors, fell into the tray, and the fine focal spots on the surface were like wind erosion lines in the Taklimakan desert.

Second, the taste genes of nomadic civilization

The shape of baked buns hides the survival wisdom of nomadic people. The quadrilateral structure is not only convenient to attach to the pit, but also symbolizes the awe of the square world. The application of dead dough originated from the demand of ancient business travelers for portable dry food, which can be stored on hunchbacks for half a month without being bad. The addition of sheep tail oil is not only a flavor code, but also a survival strategy to cope with extreme cold. Every bite of oil is an energy reserve for crossing the Gobi.

On Bazaar in Hotan, the steamed stuffed bun chef will brush the egg yolk liquid on the surface to form a golden red luster; The craftsmen in Kashgar carved diamond patterns with needles to allow the heat to penetrate evenly. These subtle differences, like the dialects of the thirty-six countries in the western regions, maintain their unique personalities in similarity. When nomads sit around the campfire and share the baked buns, the moment when the hot gravy burns the tip of their tongue is the song of their life against the harsh environment.

Third, the blending of civilizations on the tip of the tongue

Along the track of the ancient Silk Road, the baked buns have quietly changed. In Samarkand, it was wrapped in a cheese coat; In the west city of Chang 'an, Hu merchants added Chinese spices to the stuffing. Today's Urumqi night market, there is a rebellious version of crayfish stuffing, and Chili and cumin have reached a wonderful reconciliation in the dough. This kind of taste dialogue across time and space makes roasted buns a living fossil of civilization.

In the modern kitchen of the International Grand Bazaar, the infrared thermometer monitors the temperature of the pit, but the master still insists on feeling the heat with the back of his hand. Chain fast food restaurants have launched vacuum-packed baked buns, but they have never been able to replicate the soul of firewood. When urban white-collar workers cut the baked buns with knives and forks, Tajik elderly people are still grabbing food directly with their thick palms, and the two gestures are demonstrating the evolution and persistence of tradition in the same time and space.

In the old city of Kashgar at dusk, the last batch of baked buns is being taken out of the pit. The burnt incense overflowed the curtain of Adelaide silk and rose with the sound of Dutar piano. In this era of machine copying delicious food, baked buns still stubbornly maintain the original memory of the flame. Every hot triangle wrinkle seals the sun, sand and the eternal desire of human beings to fight against time in the western regions. When the tip of the tooth breaks through the brittle boundary and the hot gravy pours into the mouth, we swallow not only food, but also a whole flowing civilization epic.